Table of Contents

By 2025, AI investing has reached a fever pitch, and Nvidia stands at the center of the frenzy. The company’s market capitalization and revenues soar on the back of supposedly insatiable demand for AI hardware, driven by large-scale model training and deployment across industries. Yet financial and geopolitical evidence shows that Nvidia inflates and sustains a significant share of this demand through its own financial engineering and intertwined industry relationships. Investors, therefore, struggle to separate genuine end-user demand from circular funding and accounting maneuvers.

Nvidia’s Revenue Strategies: Cloud Credits and Artificial Demand

Nvidia’s most aggressive recent innovation lies not in chip design but in how it records revenue. Beginning in late 2022, Nvidia began structuring large deals with “cloud service providers” as non-cash exchanges. A typical arrangement works as follows: Nvidia delivers a batch of high-end GPUs to a cloud company or AI startup. Instead of receiving cash, Nvidia receives credits that it can later use to buy cloud computing time on those GPUs.

From an accounting perspective, Nvidia treats the hardware delivery as a completed performance obligation and books full product revenue immediately. The obligation to use future services is reflected in a cloud-services asset or liability that is recorded simultaneously. In essence, Nvidia exchanges hardware for cloud capacity. The firm locks in revenue and gross profit today while it pushes the associated service cost into future periods.

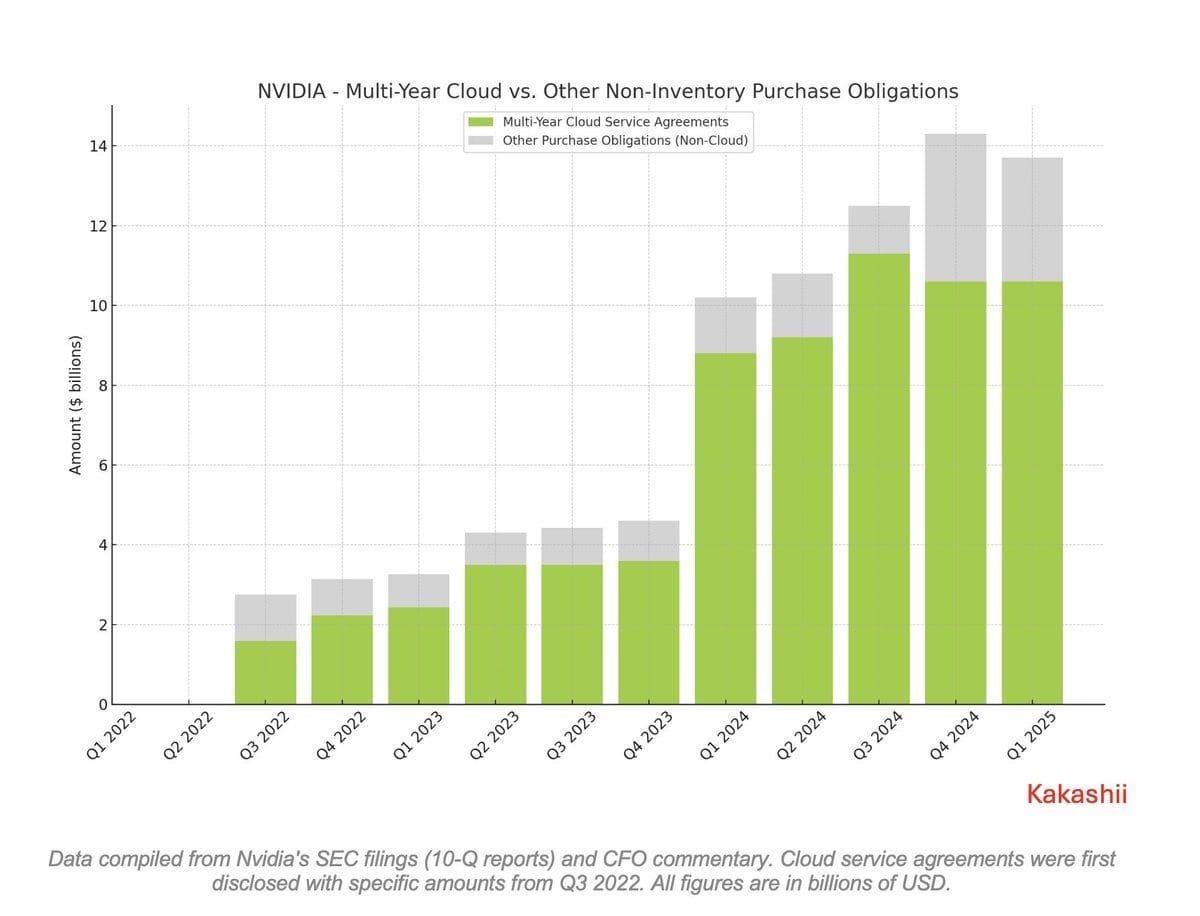

U.S. GAAP under ASC 606 permits this practice, provided the contracts specify performance obligations and enforceable rights. Yet the structure blurs the line between genuine sales and financed or barter-style transactions. Nvidia’s SEC filings since 2022 show a rapid accumulation of multi-year cloud-service purchase commitments.

Figure 1 (based on the company’s 10-Q disclosures) tracks those obligations against other non-inventory purchase commitments. Cloud-related commitments grow from near zero in early 2022 to more than $10 billion by late 2024, with peaks around $14–15 billion. [credit: Kakashii on X]

A key part of this growth stems from the agreement with CoreWeave, a cloud provider focused on AI. Nvidia agreed to buy up to $6.3 billion of unused CoreWeave capacity through 2032. The agreement effectively guarantees CoreWeave a revenue floor and simultaneously provides Nvidia with a large channel to book GPU “sales” that rely on its commitment to consume future services. Nvidia records the GPU revenue up front and recognizes the cloud capacity as a future obligation.

Nvidia’s income statements, therefore, show record revenue and margins. For Q3 FY2026 (calendar Q3 2025), Nvidia reported $57 billion in revenue, up 62% year-on-year, with GAAP gross margins around 73–74%. However, the balance sheet presents a different picture. Accounts receivable and related items swell far faster than cash. By mid-2025, one independent analysis estimated receivables at about $14 billion, roughly 68% of quarterly revenue. Nvidia’s own Q2 FY2026 balance sheet lists net receivables of $27.8 billion against $16.5 billion of quarterly revenue.

Such ratios resemble vendor financing or long-dated payment schemes rather than cash sales. Nvidia often extends generous payment terms or uses cloud-credit structures so that customers can accept more GPUs than their cash flows would usually support. These tactics pull demand forward and inflate reported growth, but they also increase the risk that some receivables and purchase commitments will never be converted into profitable use.

Nvidia applies similarly aggressive timing to license and services revenue. In some cases, it books license income when customers place binding orders, months before they take delivery of the related hardware. Large H100 orders in late 2023 led to a spike in accounts receivable, even though Nvidia had not yet shipped the chips. This pattern causes changes in top-line growth that depend more on when orders are placed than on how much computing power is actually used.

A public-sector analysis of data center project finance highlights the broader risks. The report argues that Nvidia and its closest partners have become each other’s primary sources of incremental demand, with growth numbers that rely heavily on mutual purchase commitments and prepayments. If cloud companies slow new orders, delay cloud-credit consumption, or face funding stress, Nvidia’s revenue stream will face abrupt pressure. In that scenario, previously booked revenue will not match economically justified utilization, a classic marker of bubble dynamics.

Stock-Based Compensation and Buybacks: Engineering EPS

Nvidia also exerts tight control over its equity structure. Like many Silicon Valley firms, it pays employees heavily in stock-based compensation. In fiscal 2025 (year ended Jan. 2025), Nvidia recorded $4.74 billion in SBC expense, a 33% increase from the prior year. SBC does not consume cash; instead, it issues new shares, diluting existing holders.

Jensen Huang and Nvidia’s board respond with huge stock-repurchase programs. Huang has publicly described buybacks as a mechanism to offset dilution from employee stock issuance. In the first half of fiscal 2025, Nvidia returned $15.4 billion to shareholders through buybacks and dividends. Over the first nine months of fiscal 2026 (Feb–Oct 2025), that figure reached $37 billion. In August 2025, the board authorized another $60 billion in repurchases to keep the program running.

These numbers place Nvidia among the most aggressive buyback practitioners in corporate history. The company spends more on repurchases and dividends than it earns in net income during some periods. Despite ongoing SBC issuance, the share count barely grows because Nvidia retires shares almost as fast as it creates them. This strategy boosts earnings per share, supports valuation multiples, and signals confidence to the market.

Timing adds to the effect. Nvidia frequently buys shares during windows that bracket major earnings releases. The company executes those trades under prearranged Rule 10b5-1 plans, but the practical outcome still involves large purchases around news that drives the stock higher. Insiders who receive SBC can sell shares into a market that Nvidia itself supports, while public shareholders bear the risk that the repurchased shares may later lose value.

SBC remains large even in single quarters. In the most recent filings, the expense exceeded $1.6 billion in a quarter, and Nvidia acknowledges that SBC will remain at high levels. The firm, therefore, commits to ongoing repurchases to keep dilution in check. It funds those repurchases with cash from operations and, at times, with new debt, essentially leveraging the balance sheet to feed the market’s appetite for its stock.

This loop of SBC and buybacks reinforces the revenue-side financial engineering. High reported growth and margins justify a lofty stock price. The strong stock price then supports aggressive SBC and equity-linked dealmaking with partners and customers. Buybacks offset dilution and help sustain the valuation that underpins the whole system.

Strategic Investments and Circular Dealmaking

Nvidia does not limit its activity to arm’s-length transactions. It also acts as a venture investor and strategic financier across the AI ecosystem. The firm embeds itself across the stack: in hyperscale clouds, specialist GPU clouds, AI labs, and application-layer startups.

CoreWeave illustrates the pattern vividly. Nvidia acquired a roughly 7% equity stake in CoreWeave in 2023 and agreed to the previously mentioned $6.3 billion guarantee for cloud capacity purchases. CoreWeave then placed enormous GPU orders; one 2023 transaction involved about $2.3 billion of H100s financed with a loan secured by those chips. By early 2025, more than 60% of CoreWeave’s revenue came from just two customers: Microsoft and Nvidia. Nvidia therefore acts simultaneously as CoreWeave’s supplier, major shareholder, and anchor customer. Nvidia finances the buildout, CoreWeave purchases Nvidia hardware, and Nvidia is prepared to rent the resulting GPU capacity.

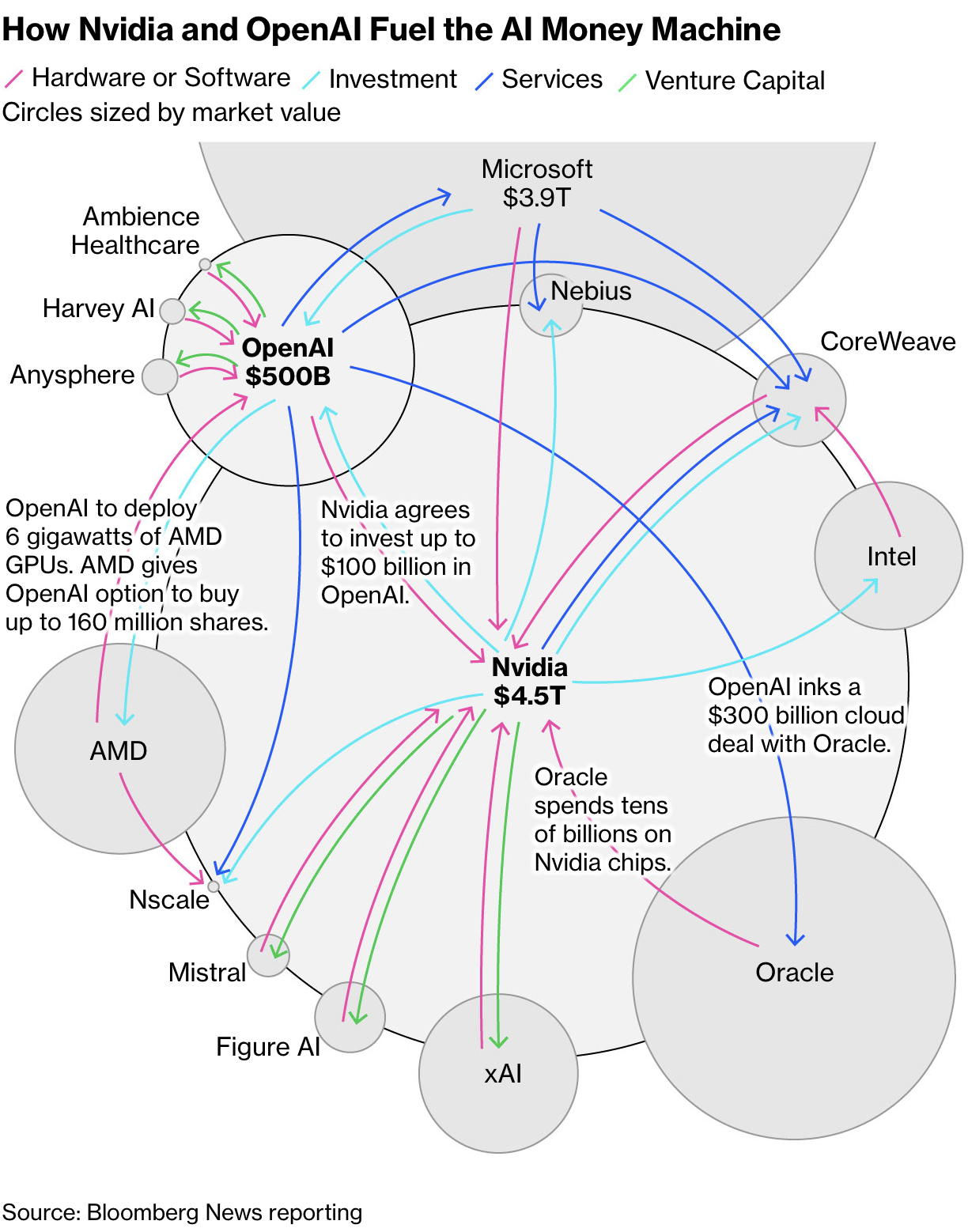

Nvidia has pursued similar entanglements with OpenAI, xAI, and other labs. OpenAI’s insatiable need for computers makes it one of Nvidia’s most important clients. Reports in late 2023 described a tentative $16 billion deal for OpenAI to purchase Nvidia GPUs for a new supercomputing cluster. By October 2025, Bloomberg reported that Nvidia had agreed to supply and invest up to $100 billion in OpenAI’s computer infrastructure as part of a broader fundraising package.

OpenAI, in turn, struck a $300 billion, eight-year cloud contract with Oracle that relies heavily on Nvidia GPUs. Oracle spends tens of billions of dollars on Nvidia hardware, not only for OpenAI’s workload but also for other AI clients. Oracle co-founder Larry Ellison has a substantial ownership stake in Nvidia and benefits when this spending boosts Nvidia’s valuation. Meanwhile, Microsoft maintains roughly a 49% economic stake in OpenAI and purchases vast quantities of Nvidia GPUs for Azure.

Figure 2 (from Bloomberg) charts this network of relationships. Arrows show how hardware, investment capital, and service commitments circulate between Nvidia, OpenAI, Microsoft, Oracle, CoreWeave, xAI, and a host of smaller AI startups. Each node in the network both buys Nvidia hardware and receives funding or strategic support from Nvidia or Nvidia-aligned investors.

Financial Times columnist Bryce Elder captured the structure with his “roundabouting” metaphor. He asks readers to imagine a caravan maker that sells caravans to parks it finances, which then buy more caravans from each other. Everyone reports growth and profits, even though the same pool of capital continuously rotates. Elder concludes, “Sorry, not caravans. GPUs.”

The analogy highlights a key point: Nvidia often sells to entities that exist mainly to buy Nvidia GPUs, frequently with Nvidia’s own financial backing. These headline deals and valuations create a powerful narrative of exponential AI demand. Yet the underlying economic exposure concentrates in a relatively small group of interdependent firms that all rely on future end-user revenues that remain uncertain.

A policy report on financing data center projects describes these intertwined commitments as risk-sharing arrangements where one company’s future growth serves as collateral for another’s leverage. If OpenAI can’t make money from its models, if Oracle or Microsoft runs into political or financial issues with spending, or if CoreWeave can’t attract paying clients for its GPU cloud, Nvidia will feel some of the effects through canceled orders, unused cloud credits, or requests on its purchase guarantees. The structure, therefore, magnifies both upside and downside. As long as investors believe the AI boom will continue indefinitely, the network amplifies demand. If confidence falters, the same network will transmit stress just as efficiently.

Geopolitical Dependencies and the Trump Administration’s Role

Nvidia’s recent growth also rests on geopolitical positioning. The firm operates at the center of U.S.–China technology competition, and U.S. policymakers increasingly treat AI infrastructure as a strategic asset. Nvidia leverages this environment, sometimes by exploiting gaps in export-control rules and sometimes by aligning directly with U.S. strategic initiatives.

China’s demand is routed through Singapore.

In October 2022, the U.S. government restricted exports of advanced AI chips, such as Nvidia’s A100 and H100, to Chinese entities. Publicly, these reforms appeared to cut off one of Nvidia’s largest markets. Nvidia responded by developing downgraded chips for China, but an even more critical channel emerged: Singapore.

Nvidia’s 2024 fiscal filings show a dramatic surge in revenue booked for Singapore. The jurisdiction accounted for nearly 28% of Nvidia’s revenue, about $17.4 billion, up several times year over year. At the same time, Singapore’s trade minister disclosed that physical shipments of Nvidia products to Singapore represented less than 1% of Nvidia’s global revenue. The discrepancy indicates that entities in Singapore placed orders that Nvidia recorded locally while they redirected most of the hardware to other countries, likely including China.

Chinese technology firms and intermediaries set up Singapore entities to exploit the gap between the billing address and the end-use location. Nvidia acknowledged in its filings that it classifies revenue by billing address, revealing that most shipments associated with Singapore revenue were actually sent to other places. For much of 2023 and 2024, this policy allowed Nvidia to serve Chinese customers indirectly, even as U.S. trade statistics showed little evidence of it.

By 2025, U.S. agencies began tightening enforcement. Investigators focused on Megaspeed, a Singapore-based company with deep Chinese ties that bought roughly $2 billion in Nvidia AI GPUs and offered access to Chinese firms. Megaspeed allegedly routed chips through a U.S. subsidiary of Inspur, a blocked Chinese server maker, and then moved them into data centers in Malaysia and Indonesia to provide cloud access back to China. When U.S. inspectors visited one Malaysian site, they found Nvidia systems still in crates, ready for re-export.

Nvidia insisted that its compliance checks showed no Chinese ownership at Megaspeed. Critics pointed to public records that revealed clear Chinese connections and argued that Nvidia chose not to investigate too deeply while the channel boosted its revenues. As investigations expanded, Megaspeed stopped placing new orders and wound down operations.

Soon afterward, Nvidia changed how it reports geographic revenue. Starting with late-2025 filings, the company began classifying revenue by the customer’s headquarters location rather than by billing address. Under the new method, Singapore’s share of revenue shrank dramatically, and more revenue appeared under China and other jurisdictions. Nvidia claimed the change provided a more accurate picture of geographic exposure.

Export approvals to Gulf allies under Trump

While enforcement targeted China-linked channels, the Trump administration moved in the opposite direction toward friendly regimes. Trump and his advisers framed AI investment as a new kind of arms race and treated Nvidia as a core supplier of strategic infrastructure.

In late 2025, reports revealed that the U.S. Commerce Department, under pressure from the Trump White House, planned to approve exports of up to 70,000 advanced Nvidia and AMD AI chips to the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. The package envisioned approximately 35,000 Nvidia GB300-class servers for each of two entities: G42 in Abu Dhabi and Humain, a new Saudi AI company backed by the Public Investment Fund.

The administration attached contractual safeguards to the deal, including audit and end-use monitoring requirements intended to prevent diversion to China or other adversaries. Yet the strategic signal dominated. Trump personally lobbied Gulf leaders to secure the agreements and characterized large-scale chip projects and foreign high-skill labor as components of his “MAGA” industrial growth strategy. The administration presented AI mega-data centers in allied states as extensions of U.S. power rather than as risks to export-control coherence.

These shipments, if fully executed, would rival the GPU inventory of some of the largest U.S. hyperscale data centers. They also align with Saudi Arabia’s plan to become an “AI superpower.” This aligns with the UAE’s efforts to establish itself as a regional AI hub. Nvidia’s partnership with Humain fits squarely within that vision, focusing on 500-megawatt AI data center buildouts in Saudi Arabia.

U.S. policy, therefore, supports Nvidia’s expansion in two ways. First, it allows, and even encourages, massive chip sales to friendly regimes, which sustains high utilization at Nvidia’s fabs and its foundry partners. Second, it frames the AI buildout as a national defense and foreign policy priority. With that framing, regulators show little appetite to scrutinize Nvidia’s financial engineering or circular demand structures. Policymakers treat the AI bubble as a mechanism that channels private capital into defense-relevant infrastructure without direct fiscal cost.

Conclusion: Bubble Dynamics, Geopolitical Risk, and the Oversight Gap

Nvidia’s rise during the 2025 AI boom illustrates how corporate finance, venture ecosystems, and geopolitics can converge to inflate a bubble. Through cloud-credit deals, aggressive licensing recognition, and long-dated purchase commitments, Nvidia pulls future hardware demand into current revenue. Through heavy SBC and buybacks, it converts that reported growth into ever-higher earnings per share and supports a towering market valuation. Through strategic investments and reciprocal contracts with CoreWeave, OpenAI, Oracle, Microsoft, and others, it embeds itself in a self-referential network where each firm’s growth both depends on and validates the others. Finally, by exploiting loopholes in export controls and aligning with Trump-era industrial and security policy, Nvidia ensures that geopolitical imperatives reinforce rather than restrain its expansion.

These dynamics create enormous upside as long as AI adoption continues to accelerate and capital remains cheap and plentiful. They also concentrate risk. If AI workloads fail to generate commensurate revenue, many GPU clouds will sit underutilized while cloud-credit balances and purchase guarantees come due. In that scenario, Nvidia will face order cancellations, write-downs of cloud-service assets, and pressure on its margins and cash flows.

Geopolitical shifts could deliver additional shocks. A sharper U.S.–China confrontation might close remaining loopholes and restrict demand from intermediaries. A future administration could rethink the wisdom of large-scale chip exports to Gulf regimes or impose more stringent reporting and compliance obligations. Domestic regulators such as the SEC could revisit revenue recognition rules for non-cash transactions and place guardrails on buybacks during periods of extreme market exuberance.

For now, none of these constraints meaningfully limit Nvidia. The company occupies a privileged position as the perceived backbone of American AI power, and the Trump administration’s rhetoric and export decisions reinforce that status. Market participants, therefore, treat Nvidia not just as a dominant supplier but as a strategic national asset. That perception further reduces the likelihood of timely regulatory intervention, even as classic signs of a bubble accumulate.

Whether policymakers and investors manage the eventual correction smoothly or confront a disorderly collapse will shape not only Nvidia’s future but also the trajectory of the broader AI ecosystem and the economic strategies of the United States and its rivals.