Table of Contents

A flesh-eating parasite straight out of a horror movie has made its way to American soil, courtesy of a traveler from Central America.

With our southern border wide open and pests like this creeping north, it's a wake-up call for the bureaucrats in Washington who seem more focused on politics than protecting our people and our livestock.

In a development that has sent shockwaves through the U.S. beef industry, federal health officials have confirmed the nation's first travel-associated human case of New World screwworm – a parasitic fly infestation that devours living flesh – in Maryland.

The patient, who recently returned from El Salvador amid an ongoing outbreak there, was diagnosed after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reviewed images of larvae extracted from the infection, confirming the case on August 4, 2025.

The Maryland Department of Health collaborated with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention on the investigation, marking a rare human incidence of this pest, which is far more notorious for ravaging livestock in tropical regions.

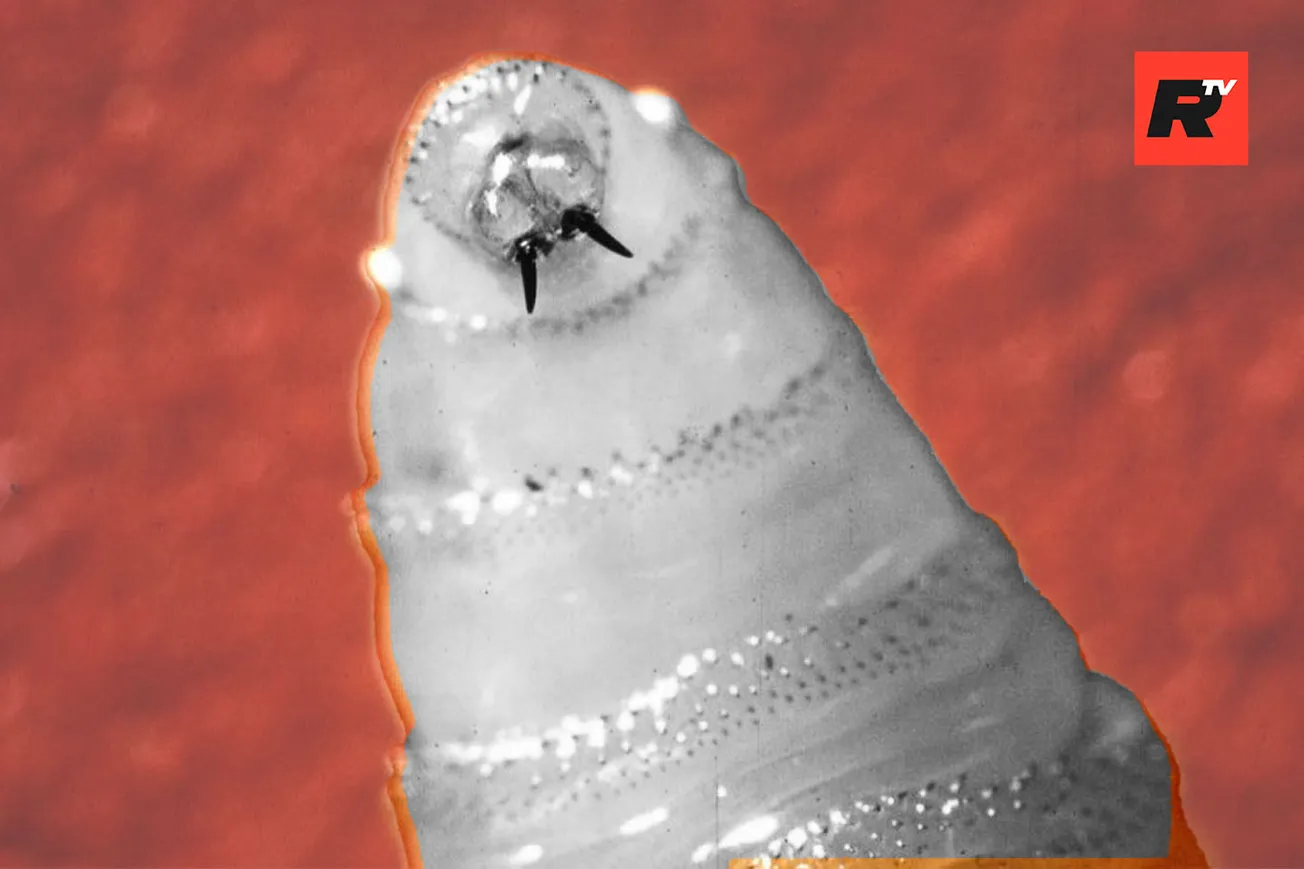

New World screwworm, scientifically known as Cochliomyia hominivorax, involves female flies laying eggs in open wounds, noses, or ears of warm-blooded hosts, including humans.

Once hatched, the larvae burrow into tissue with screw-like mouths, feeding on live flesh and creating expanding lumps that can prove fatal without prompt intervention.

Transmission can also occur indirectly via ticks or mosquitoes carrying the eggs. Treatment is grueling, requiring manual removal of potentially hundreds of maggots and thorough wound disinfection, but outcomes are generally positive if addressed early.

The CDC emphasizes that myiasis—the medical term for such larval infestations—is uncommon in the U.S., with most diagnoses linked to travel in endemic tropical areas.

Andrew G. Nixon, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told Reuters in an email: “The risk to public health in the United States from this introduction is very low.”

Despite this reassurance, no cases have been reported in U.S. animals this year, a critical point for an agriculture sector already bracing for potential catastrophe.

Complicating the narrative is a glaring discrepancy in the reported origin of the infection.

Official HHS and CDC accounts pinpoint El Salvador as the patient's travel destination, but beef industry sources initially informed stakeholders that the traveler had arrived from Guatemala – another nation grappling with the outbreak.

Nixon declined to address the conflicting reports, fueling frustration among livestock producers and veterinarians who accuse federal agencies of opacity.

Beth Thompson, South Dakota's state veterinarian, revealed to Reuters that she learned of the Maryland case indirectly last week from a knowledgeable source, not through official channels.

"We found out via other routes and then had to go to CDC to tell us what was going on," Thompson said. "They weren’t forthcoming at all. They turned it back over to the state to confirm anything that had happened or what had been found in this traveler."

Another anonymous source confirmed that state veterinarians were briefed on the human case during a CDC call, while a Maryland state official also verified its existence.

The revelation has amplified anxiety in the cattle ranching, beef production, and livestock trading sectors, already on high alert as screwworms advance northward from Central America through southern Mexico since 2023.

Endemic in countries like Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and parts of South America, the parasite prompted Mexico to report a fresh case in July 2025, just 370 miles south of the U.S. border in Veracruz, leading to repeated closures of livestock trade through southern ports since November 2024.

The U.S. typically imports over a million Mexican cattle annually for fattening and slaughter, a flow now disrupted amid these precautions.

Economic stakes are staggering: The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates a full-blown outbreak in Texas—the nation's top cattle-producing state—could inflict $1.8 billion in damages from livestock losses, labor, and treatments.

With U.S. cattle herds at their smallest in seven decades and prices at record highs, traders are jittery.

In emails reportedly circulated last week by a Beef Alliance executive to about two dozen industry insiders the case was described with limited details due to patient privacy laws, noting the individual was treated and state prevention protocols activated.

The CDC notified Maryland health officials, the state veterinarian, and other agriculture stakeholders, per the emails.

"“We remain hopeful that, since awareness is currently limited to industry representatives and state veterinarians, the likelihood of a positive case being leaked is low, minimizing market impact," the executive wrote:

Additionally, a Texas A&M University livestock economist was tasked with assessing the border closure's industry fallout for USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins.

In response, the USDA has ramped up defenses.

Secretary Rollins visited Texas on August 15, 2025, to reiterate plans for a sterile fly production facility at Moore Air Force Base in Edinburg, initially announced in June 2025, though it may take two to three years to operationalize.

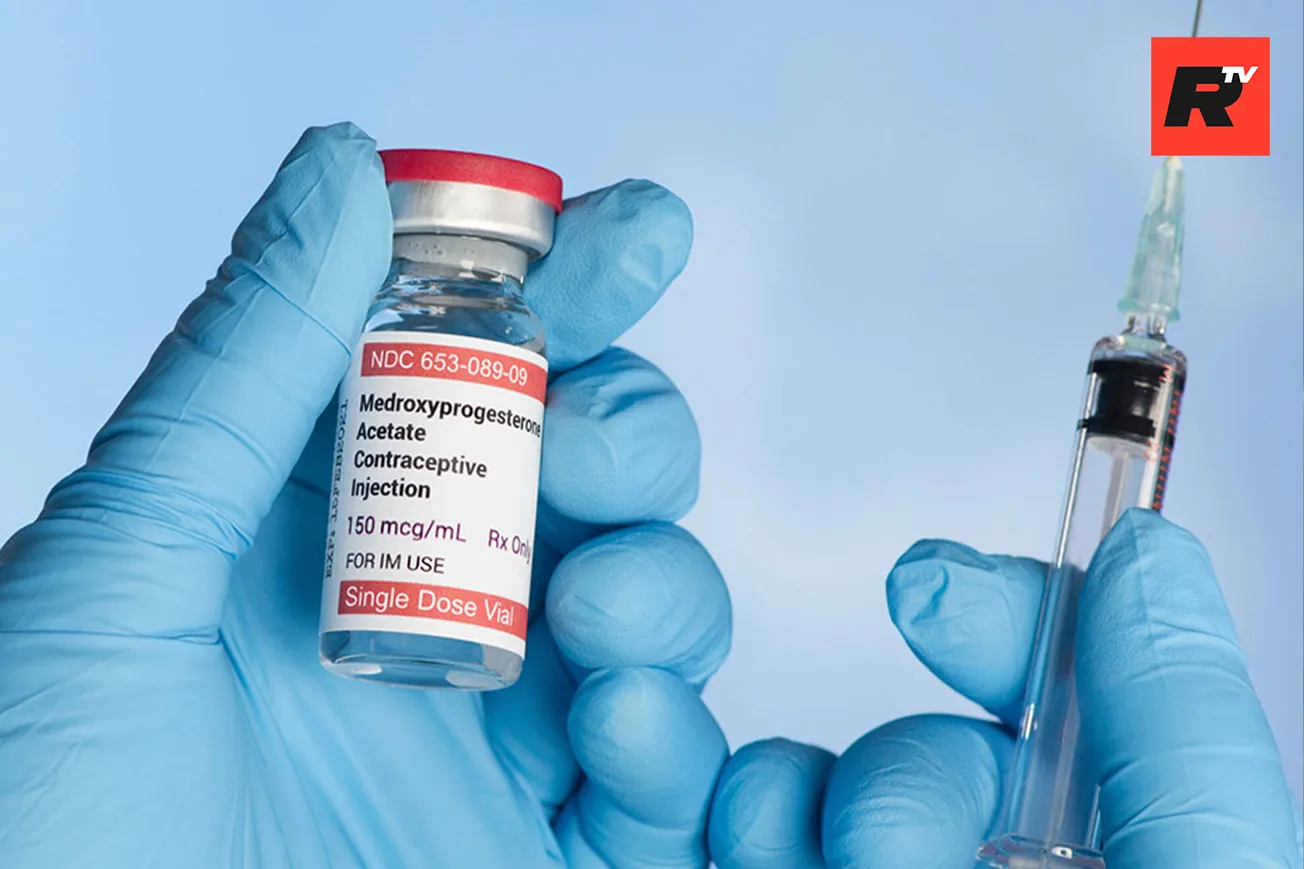

This technique, pioneered in the 1950s, involves releasing irradiated sterile male flies to mate with females, preventing reproduction and eradicating populations. The sole current facility in Panama produces up to 100 million sterile flies weekly, but the USDA deems 500 million necessary to repel the pest back to the Darien Gap.

Mexico is constructing a $51 million plant in its south, while U.S. efforts include border traps and mounted patrols—measures criticized by producers as belated.

The agency faces political heat for perceived delays in bolstering fly production amid the northward march.

With a single human case exposing cracks in federal transparency, and billions hanging in the balance for America's heartland ranchers, the real infestation may be one of complacency.

Will the sterile flies take flight in time, or will this parasite drill its way into our economy? For now, the patient in Maryland is on the mend and the animals remain unscathed.